Mental Health Clinical Leadership, Recovery, Accountability, and Integrated Care

Now more than ever mental health providers need strong clinical leadership, service accountability and improved outcomes for patients. ‘We have seen the complexity of patients coming through services,’ said Dr Jo Emmanuel, former Medical Director at one of the UK’s largest mental health providers. Even before the pandemic, the NHS was set to invest an extra £2.3bn annually in mental health services by 2023: that’s enough to see two million more patients per year, says Claire Murdoch CEO CNWL.

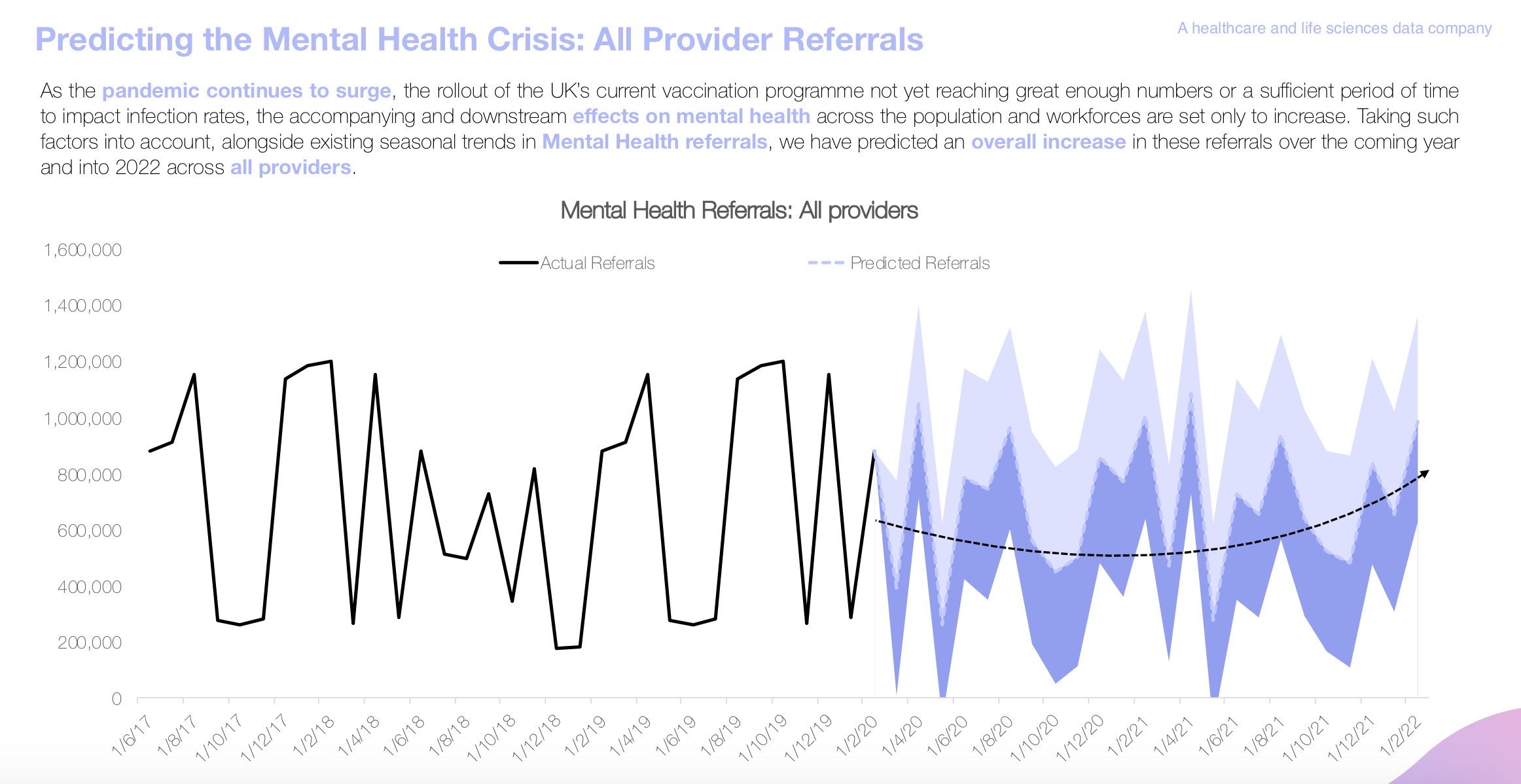

The latest mental health data shows many providers are still struggling with patients being placed out of the locality of their main provider, which is something that NHS England focuses on avoiding as it is ultimately detrimental for patient care. Data provided by RwHealth’s AI platform predicted the increased demand witnessed over the past year, and that this will likely continue into early 2022:

We sat down with Dr Jo Emmanuel to discuss the role of clinical leadership accountability and integrated care in the recovery efforts.

Dr Jo Emmanuel is a psychiatrist with a focus on adult mental health in inner London where she transferred her extensive experience as a consultant to the role of Medical Director. Her division supported a population of over a million with 2000 staff and her role entailed holding the division to account, clinical governance, clinical leadership, and linking in with the emerging ICSs.

She has technically taken early retirement but is still working in various roles within the mental health sector

The current mental health landscape

The mental health system endlessly battles to balance acute crisis care and community preventative care. The pressure on acute care often takes centre stage, but this can easily lead to preventative care being neglected.

‘There’s a great risk that we will direct more of a narrowing budget towards acute at the expense of the wider picture.’

To better support the nation’s mental health, there needs to be greater emphasis on addressing the causes of poor mental health and supporting people before they reach crisis stage. The social determinants of inequality and unhappiness must be addressed rather than just focusing on their consequences. Shifting focus won’t be easy, but it’s the only way to get the sector off its current defensive footing.

Changes to the landscape in the coming months.

Despite the stigma surrounding mental health decreasing in recent years, mental health remains an uncomfortable subject for many. Things like anxiety and depression have become more socially acceptable, but more complex issues like psychosis and substance abuse remain in the shadows.

If headlines are to be believed, mental health demand is increasing all across the sector, but data has shown this is not consistently the case. In fact, some referrals plummeted during the pandemic. Data insights have been absolutely vital here as staff are likely to report being as busy as ever – this can be attributed to staff shortages and deep exhaustion that makes it hard to be objective.

‘Some people are using services less, but pockets of the population have been massively affected, such as the elderly, young people, ethnic minorities, and women. Going forward, we’re going to see that differing impact in everything from economic burden to mental health.’

The sector will have to be nuanced and tailored in its response and detailed data will be required to ascertain where the demand really is. As we head out of the pandemic, the scramble for funding is likely to get even harder as serious questions are asked about how we deliver care going forward. We have been catapulted into virtual delivery and adapted out of necessity; it’s time to adjust delivery so that it truly benefits staff and patients in terms of speed and quality of outcomes.

Virtual delivery is here to stay, at least as an option. This isn’t a bad thing as it opens up flexibility for patients and for staff. ‘You can’t do all mental health care remotely, but you can do more than we think.’

Data in mental health recovery

Data makes it possible to see the forest for the trees; instead of getting lost in the details, providers can accurately assess the whole system and make informed decisions about how to move forwards.

Demand routinely outstrips capacity, irrespective of the pandemic. With this in mind, data can help direct limited capacity where it’s needed most, allowing inequalities to be assessed and the most in need patients to be identified. Data also provides quantifiable reasons for implementing changes, making changes easier to pitch to staff – especially those which might meet resistance or require a culture shift.

This overview of pressure points will be integral in addressing current waiting lists and allocating precious resources where they are needed most. With a comprehensive grasp of their data, teams will be able to identify their highest need users and implement tailored interventions.

When COVID hit, data insights enabled teams to rapidly prioritise their most vulnerable service users. By stratifying their lists and assessing waiting times, staff were also able to quickly identify those who had slipped through the net:

‘The data helped us say “Are these people in need of our service and not getting it? Is it an admin error? Or has something gone wrong?”

From assessing that data, they were able to set new performance targets and revaluate the newly apparent flaws in their system:

‘It’s clear we have to think differently about how we work with the voluntary sector, and what we do to support people before they even reach our services. With much less emphasis on the referral machinery and more around relationships – we stand a better chance.’

The sector’s mental health

Although demand has gone down in some services, this has offered little respite for staff:

‘Staff are tired, they’re probably traumatised, they’ve lost colleagues, and just like the rest of the population, all their normal coping mechanisms have been restricted. Almost 20% have family abroad that they haven’t been able to go and see. The lack of PPE was a crisis, and now the compulsory wearing of it is another challenge. We can’t underestimate just the impact this has had; the pressure has been relentless.’

The trust does as much as they can to support staff, but those who need support the most are the least likely to have the time available to access it.

On top of this, there have been staffing gaps; recruitment in mental health is at a critical point. Teams in central London that were previously the most popular places to work are seeing staff leaving in droves. Having robust recruitment systems in place to counteract this is critical. As a sector, we need to think about what sustainable recruitment and supporting staff truly looks like.

‘Despite this, there is much to be positive about. I think mental health services responded incredibly well to the challenges posed by the pandemic including working collaboratively across traditional boundaries with colleagues across the system. As ICSs develop, I hope this continues and we can play a central part in delivering truly holistic population-based care.’